A collection of stories on Marcos treasury

The Marcos treasury is an open secret.

When the Marcoses were in power, the entire Philippine economy lay in the palm of their hands. Anything the country earned - be it taxes, tariffs, land sales, etc. - could end up in their pockets. Furthermore, they gave many exclusive deals to their cronies and bestowed upon them lucrative concessions to minerals, timber and cash crops. It would be naive to think that the Marcoses did not receive a kickback, or share of the profits, in such schemes.

In the year 1999, when the Marcoses had returned to the families and settled once more, Imelda boldly declared that they owned "virtually all of the Philippines".

This article is a collection of stories about the Marcos treasury - stories of recovery and of failure, showcasing the brains and brawn of the Marcoses and proving that in most (if not all) cases, they are one step ahead.

1. The Yamashita Treasure

A widely circulated story (that some consider to be a mere conspiracy theory) concerns a three-foot-high Golden Buddha, stuffed with diamonds, gems, and accompanied by hundreds of gold bars and other valuables accumulated by Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita throughout the course of World War II as booty. It was hidden shortly before the end of the war. A poor locksmith allegedly found the Buddha and the gold in a tunnel near a hospital in 1971, only to have it all seized by Marcos and stored away in a Swiss Vault. Later, a Swiss court in Zurich ordered Imelda, as the heir of her husband's fortune, to pay the locksmith's family $460 million. Whether she has actually paid this is uncertain.

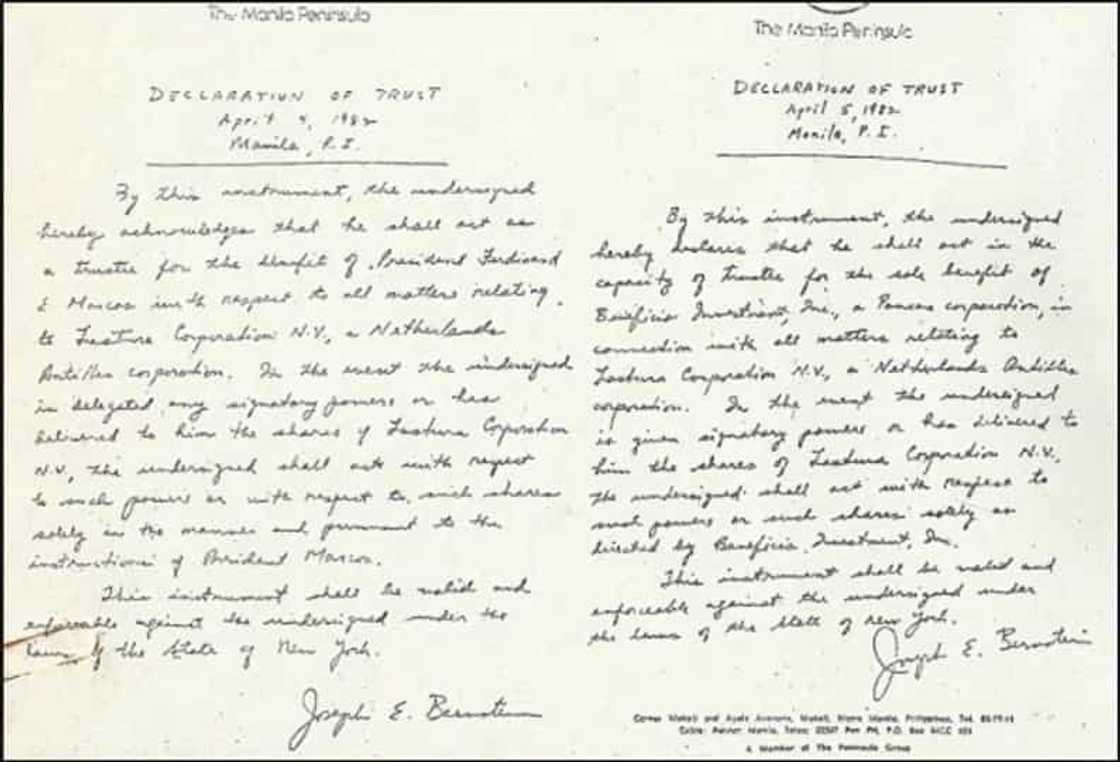

2. The Bernstein Brothers

While the Marcoses were hastily packing up for their departure, some of their documents and other items fell on the floor. Two of these documents were later discovered to be the "smoking gun" evidence (a term used to refer to an object or fact that serves as conclusive evidence of a crime) that soon led to the recovery of four buildings in New York worth $350 million.

The documents were declarations of trust, handwritten by Joseph Bernstein. The first declaration of trust, dated, April 4, 1982, declared that Bernstein, a New York real estate broker, would act as trustee for ex-president Marcos with respect to Lastura Corp NV, a corporation registered in Netherlands Antilles.

The second declaration of trust, dated April 5, 1982, stated that Bernstein was the trustee of Beneficio Investment Inc, a corporation registered in Panama. It, in turn, owned Lastura Corp.

With this in the government's hands, the Bernstein brothers Joseph and Ralph admitted to fronting the Marcoses for the purchase of the New York buildings.

3. The yellow stains on the Marcos treasury

The recovery of the Marcos loot is tainted by the greed of the ones behind it as well.

An interesting testimony from Dr. Teresita Reyes, Margarita "Tingting" Cojuangco's dermatologist (Margarita is the wife of Jose "Peping" Cojuangco, Cory Aquino's brother) was released during the 1991 trial in New York, concerning the racketeering case against Imelda Marcos.

It was about several Louis Vuitoon valises containing jewelry that they had taken out of Imelda's bedroom.

The valises were placed in vans that drove to Reyes' house in Dasmarinas Village, Makati. A few members of the Reformed Armed Forces Movement saw the valises being loaded into the van, and then reported to the then Defense Minister Juan Ponce-Enrile.

Enrile reportedly hurried to the Dasmarinas destination, and walked in on the society matrons excitedly, like children, trying on Imelda's jewelry.

Those jewelries (no-one's sure if everything was really accounted for) are now in the possession of the Central Bank and are called the Malacanang collection.

Lately, Kris Aquino has been accused of keeping and wearing several Marcos jewelries as well. However, the PCGG debunked this, saying that she did not have any access to the jewelry.

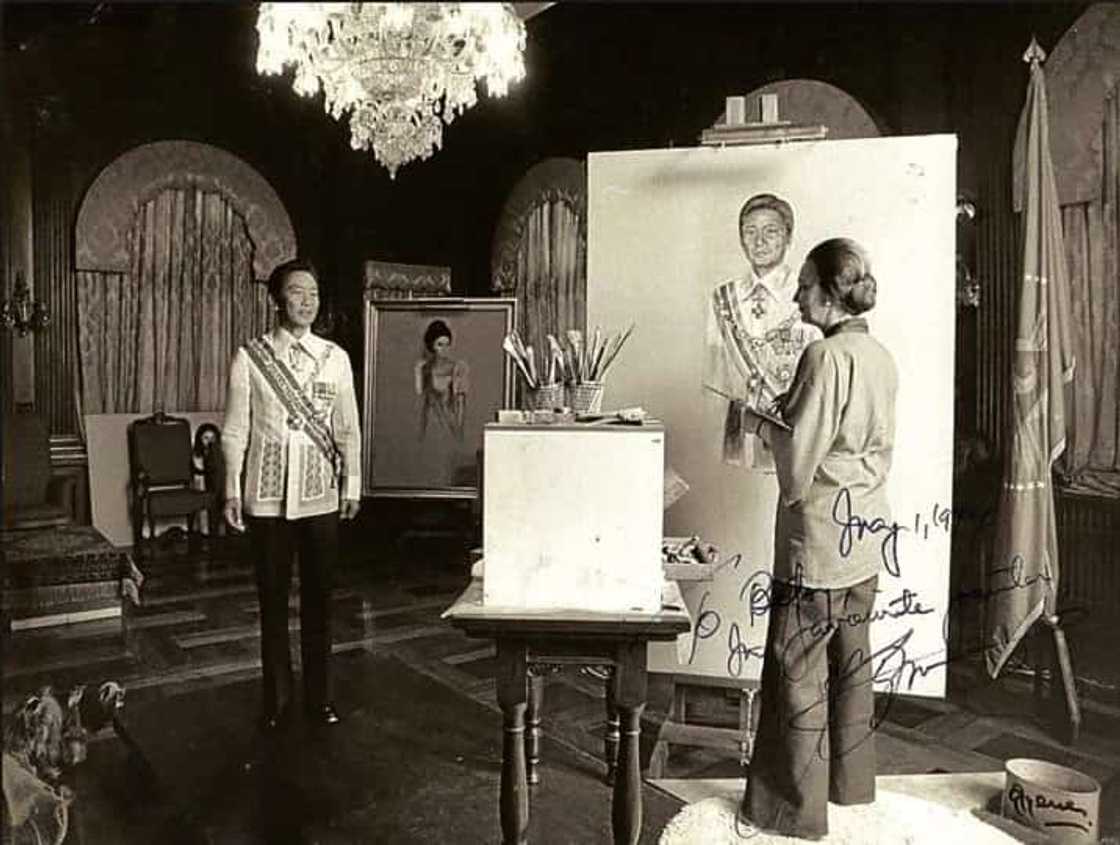

4. The infamous Marcos paintings

Let's end with a well-known investigation gone awry: the Marcos paintings.

After the Marcoses fled the palace, the PCGG noted that the ballroom walls displayed 23 prominently pale patches, where masterpieces once hung.

The family owned a town house on East 66th Street, New York, where Imelda liked to hold her parties. The neighbours revealed that they had seen two 18-wheel trailers pull up a few days after the couple fled into exile. It had been filled with antiques and paintings, and then driven away. When the house was searched a few days latter, only the brass plaques that boasted of the treasures that once occupied the walls remained - Madonna and Child by Michelangelo, Marquesa de Santa Cruz by Goya, a few Monets, two Braques, a Manet and A Pissarro.

Paperwork retrieved and compiled from their various homes uncovered at least 304 valuable paintings purchased by the Marcoses. Nearly all of them were now missing.

The PCGG managed to have a judge order galleries and auction houses to not sell anything that may have come from the Marcoses. There was not much more they could do.

However, Oscar Carino, former manager of the New York branch of the Philippine National Bank, helped push the case forward: in a sworn statement, he claimed he had created accounts for two bogus companies that would help conceal the Marcos millions.

It was soon uncovered that the paintings had changed hands with a little help from some powerful connections. Rumor had it that some part had been played by Adnan Khashoggi, the infamous Saudi arms dealer. An Australian TV programme claimed dozens of Marcos paintings had been sent out of the US on a private plane, and 38 others had been shipped form Hawaii.

The French police, upon request from the PCGG, raided two of the arms dealer's apartments and found paperwork confirming that the masterpieces were indeed in his hands.

Khashoggi argued that he had made bona fide purchases from the couple, but US authorities soon concluded that the documents he produced to back his claim had been backdated. He was formally accused of obstructing the course of justice.

He was arrested in Switzerland and extradited to New York, where he joined the Marcos couple and several others indicted under the anti-racketeering law. However, Ferdinand Marcos died in September 1989, before the case came to trial - he was 72 and had been in a Honolulu hospital for months.

Without Marcos, some crucial evidence became inadmissible. There were reports that the White House was urging the prosecutors to go soft, that there was too much potential humiliation for the last five US presidents. Imelda pleaded, saying she was "a poor widow who knew nothing about her husband's activities". Khashoggi protested innocence and was acquitted of any offence.

The case ended on July 1990, with all the defendants declared not guilty on all counts.

US authorities agreed to not take any further legal action if Khashoggi surrendered the paintings and skyscrapers. But when the skyscrapers were finally sold, it was discovered they had been heavily mortgaged by the Marcoses. The city called for unpaid property taxes. The building's total sale price was $50m, but the Filipinos only received $5.7. The dozens of paintings Khashoggi was believed to have handled were no longer in his possession. The PCGG only retrieved 26.

This was, doubtlessly, a frustrating journey for the investigators. The PCGG was ordered to seize nothing, but work through the courts instead. This turned out to work in favor of the Marcoses, who had the dollars to hire the best lawyers. Dozens of cases were sidetracked by endless technical argumentation.

In addition to wealth too enormous to seize, the Marcos' influence was too widespread to beat. A New York source disclosed a report revealing that even before he was deposed, his allies in US intelligence knew that he had stolen up to $10bn. However, the CIA refused to reveal what they knew. The Japanese government heavily implied that aid packages would be in jeopardy if the PCGG nosed about too much, and that they were not going to hand over information as well. In the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher's government announced that all this was "not our business".

The reason behind their guarded countenance was simple: they had turned a blind eye while their companies had bathed in the mud alongside Marcos, receiving money without asking where it came from. In some cases, Marcos had given bribes to senior politicians and sent illegal contributions to election campaigns, such as those of US presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. When this came out in 1986, the two said they were not aware of the money's origin.

Furthermore, it appears the US never handed over all the paperwork seized from Marcos when he arrived in Hawaii. Some inventory pages have been left blank, and the PCGG believes the government may have redacted transactions involving US organizations.

In 1991, Imelda Marcos returned to the Philippines with her three children, now grown up. The PCGG in New York zoned in on rumors that some of the paintings were still there and being sold by a professional dealer. They hired a firm of investigators to keep an eye on the dealer.

However, the investigators discovered that the dealer knew they were on his trail. In June 1992, they watched as five men and women "of Filipino appearance" showed up outside the dealer's apartment with two bans, filled it up with boxes and large blue suitcases, and drove to JFK airport, where they all checked in as first-class passengers, bringing along their cargo.

The investigators had no legal power to intervene, and could do nothing else but watch as they - and the paintings, presumably - flew off to Manila.

-

Robert Sison, Imelda's lawyer, refers to the Marcos wealth as 'confiscated', rather than 'recovered' by the commission. He insists there is no legal basis to take the assets.

"The Philippine government has no right to question why Mrs Marcos had this art. Ferdinand Marcos was a gold trader before he became president, and he made his money then."

He also pointed out that despite numerous cases being filed against the family, no-one has been successfully prosecuted.

The PCGG faces huge setbacks, not just because the art is difficult to find, but also because the commission itself is not well respected. It has been stained by the very corruption it seeks to weed out. If it insists on going in, it needs the support of the public.

In addition to that, the Philippine judicial system is dreadfully slow, and several legal cases against the Marcoses and their allies have stuck in the backlog for years, never making it to court.

Source: KAMI.com.gh