How Marcos' treasury came about - and where it is now

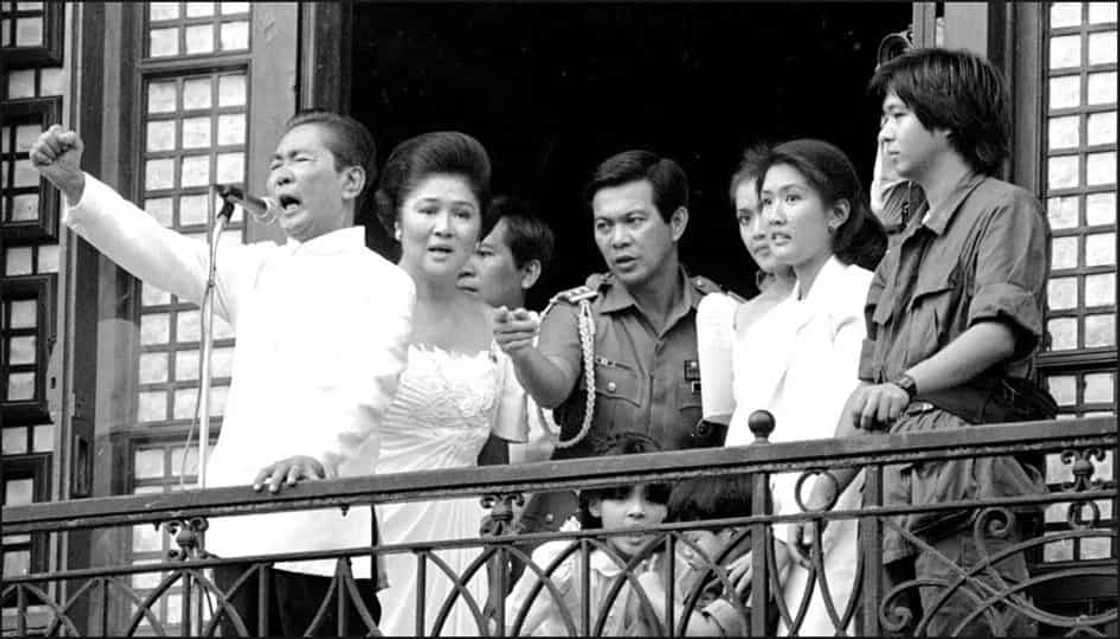

On a bright February morning in 1986, Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos fled into exile. After 21 years as president of the Philippines, Marcos' luck in the Philippines had run out. The army had turned against him, and the people had gone out onto the streets in droves. The Marcoses had seen this crisis coming, and had been able to prepare their escape accordingly. When they landed that morning at the Hickham USAF base in Hawaii, they carried possessions aplenty.

The official US customs record takes up around 23 pages. In the two C-141 transport planes that took them away, they had packed: 23 wooden crates; 12 suitcases and bags, and various boxes, the contents of which included enough clothing to fill 67 racks; 413 pieces of jewelery, including 70 pairs of jewel-studded cufflinks; an ivory statue of the infant Jesus, adornedwith a silver mantle and a diamond necklace; 24 gold bricks, inscribed “To my husband on our 24th anniversary”; and more than 27 million Philippine pesos in freshly-printed notes.

The total value was $15 million.

By anybody's standards, this amount was a fortune, and the late President Marcos' official salary had never risen above $13,500 a year, so it was painstakingly clear that this was a ridiculous amount of stolen wealth. However, the new government of the Philippines knew this was only a very small part of the Marcoses’ wealth. The shocking reality was that Ferdinand Marcos had accrued a fortune nearly 650 times greater. According to an estimate by the Philippine supreme court, he had accumulated up to $10bn while in office.

Some of his closest allies also stole billions. Seeing as their victim was an entire nation wherein 40% of the people survive on less than $2 a day, the Republic of the Philippines decided to try to retrieve the money as soon as possible.

The very first executive order issued by the new president, Cory Aquino, established the Presidential Commission on Good Government, or the PCGG. Its goal was to recover “all ill-gotten wealth accumulated by former president Ferdinand Marcos, his immediate family, relatives, subordinates and close associates” and given the power to seize any assets believed to be the proceeds of crime.

READ ALSO: A collection of stories on Marcos treasury

Thirty years later, the PCGG is still at work, with around 94 lawyers, researchers and administrators house in a building recovered from the Marcos family. The government provides an annual budget of $2.2 million. Their staff has traced money all over the world and fought their way through hundreds of court cases.

Sadly, the PCGG has recovered only a fraction of what was taken by the Marcoses and their networks. No-one has served any prison sentence for their part in the crime.

Today, its task still far from complete. To make matters worse, its longevity is threatened by a political development that the crowds who swelled the streets in triumph as Marcos fled would never have expected to happen: The late president's son, Ferdinand Marcos Jr, otherwise known as "Bongbong," is a frontrunner in the vice-presidential national elections this May 9.

RECOMMENDED: DEBATE: Should late President Marcos be buried in the Heroes’ Cemetery?

If he makes it, he would have the power to shut down the PCGG, as political allies of his family

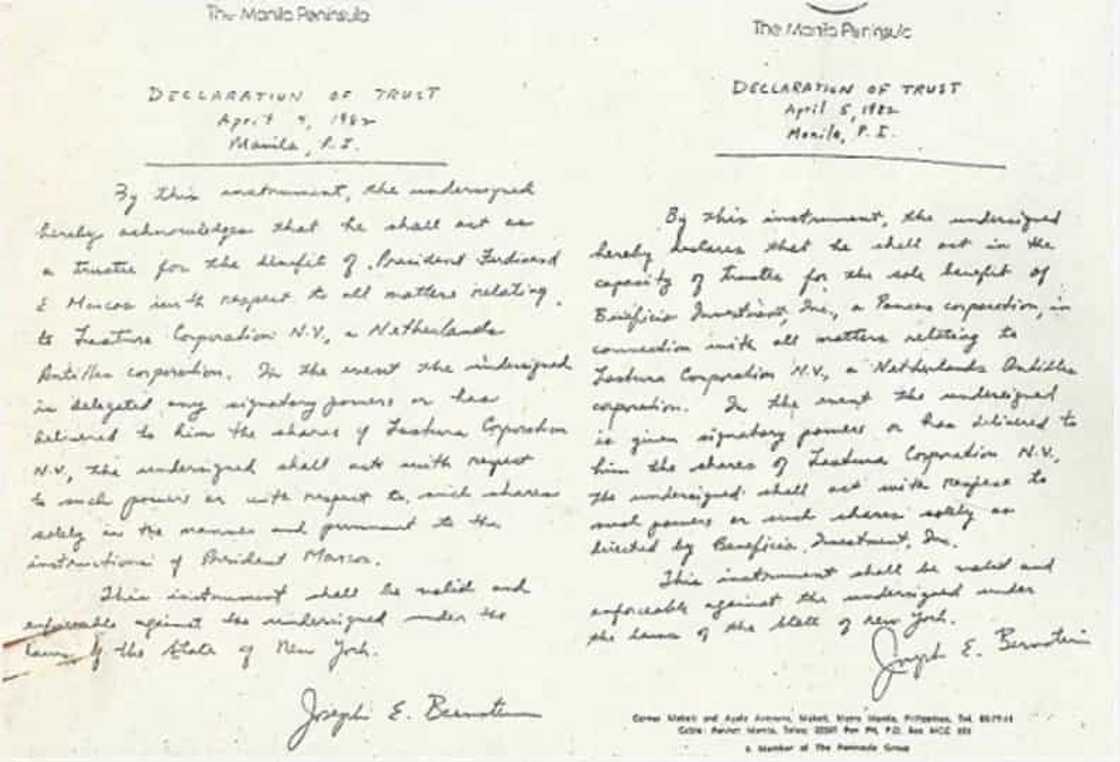

The PCGG has assembled a tremendous archive in its years of global detective work. It has the president's handwritten diary, a notepaper headed "From the office of the president," with scribbled sums continuously adding up his cash; minutes of company meetings with his personal comments written in the margins; "side agreements"; contracts; records of multiple bank accounts; hundreds of share certificates; private investigators' reports; and thousands upon thousands of pages of court judgments.

The PCGG archive paints a crystal clear picture of the story of the biggest theft in history, and of the master criminal who was behind it all. It also opens up a new perspective into the offshore world revealed by the Panama Papers. Marcos was one of the first to exploit the secret jurisdictions and hidden ownership, still in the early stages of being built away from the eyes of the public.

The story starts here.

Once upon a time, a young civil servant named Chito Roque worked his way through the crowds outside the presidential palace to the gates. He was with his boss, a senior official in the new government, and they eventually found their way into the Marcoses' private living quarters. There, they saw the signs of a hasty flight: food still warm on the dining table, empty boces, papers scattered all over the floor, shredding machines stuffed with more paper.

His boss left early, but Chito wandered into the bedroom. Once inside, “I saw a filing cabinet and I opened the first drawer and I saw a safe inside and there were numbers, a combination that was pasted on the door, so I followed the combination and opened the safe.”

Inside, he found records of bank accounts in Switzerland and Canada, share certificates and several letters signed by Marcos.

Those documents are now in the offices of the PCGG, along with thousands more that were retrieved from the palace and the 50 or so other properties the Marcoses and their allies owned in the Philippines, and from homes and offices in the US. As the years have passed, hundreds of thousands of pages have been added from several other sources. All of them are now neatly ordered and filed in a white, two-storey building near the centre of Manila.

READ ALSO: President Marcos should be buried in Ilocos Norte instead – Joma Sison

The PCGG documents suggest that Marcos, like most criminals, started out small. After becoming President in 1965, his income from kickbacks for government contracts increased, but his shady misdeeds went no further than stashing $215,000 in a New York bank in his own name.

The records show that he and Imelda took their first steps to real secrecy on March 20, 1968, when they used false names to deposit $950,000 in four accounts with Credit Suisse. He went under the name William Saunders (he practised his new signature on the headed paper), and Imedla went under Jane Ryan.

By February 1970, the Swiss accounts were so loaded, the couple added an extra layer of concealment by transferring their ownership to foundations registered in Liectenstein.

Then Marcos decided to up his ante.

September 21, 1972. The date he declared martial law. As his diary records go, the Nixon administration consented to him shutting down congress, arresting his political opponents, taking control of the media and courts, and suspending all civil rights. On the same day, he took time off to open another Swiss bank account.

A week later, while reflecting on his "reforms", Marcos wrote: "The legitimate use of force on chosen targets is the incontestable secret of the reform movement."

In the next nine years, an estimated 34,000 trade unionists, student leaders, writers and politicians were tortured with electric shocks, heated irons and rape; 3,240 men and women were dumped dead in public places; 398 others simply disappeared. With an iron grip over all politics, the president closed in on the country's wealth.

Now Marcos started to steal whole companies.

He wanted the nation's electricity company, Meralco. It was owned by Eugenio Lopez, patriarch of one of the families who had run the country for centuries. Marcos had Lopez's son charged with plotting to assassinate him, a crime which carried the death penalty. The old oligarch handed over his $400 milllion dollar company for $220.

For the most part, Marcos' takeovers involved no violence. Martial law literally allowed him to write his own laws.

When he wanted to take over the sugar industry, he started off with setting up companies and issuing decrees that allowed them to dominate the planting, milling and international marketing of Philippine sugar, which accounted for 27% of export earnings.

READ ALSO: Duterte’s closeness with Marcos is something to watch out for

Next, he created a Philippine Exchange Company, decreed that it should handle all foreign sugar sales and used its monopoly position to buy from farmers at rock-bottom prices and sell at vast profit. This allowed him to buy Northern Lines, which had the contract to shop the sugar overseas.

Finally, he decreed that the sugar industry be exempt from minimum-wage law, with the result that 500,000 labourers saw their income fall to less than $1 a day, making even more profit.

In the same way, Marcos used his own companies to take over three other key areas of agriculture: coconuts, tobacco and bananas. He craftily edged his way into dominating industries across the whole economy by granting himself government contracts, monopoly deals and tax exemptions - logging and paper, meat, oil, insurance, shipping and airlines, beer and cigarettes, textiles, hotels and casinos, newspapers, radio and TV. Predatory. Privatisation at its worst.

RECOMMENDED: In defense of Martial law: Why Marcos is a hero

He analyzed his crime through a lawyer's eyes. He noted that while people would obviously observe that the Marcoses were suddenly very wealthy, what mattered was that there would be no evidence.

He set up his companies so that externally, they belonged to other people. Marcos deployed dozens of his cronies: relatives, golf partners, political allies, anybody who shared his greed. The crony would sign a deed transferring ownership of most of the business - usually 60% - but would leave a blank space for the name. Marcos would hold the deed and leave the space blank. Technically, there was no "evidence" that he owned the 60%.

When the Japanese paid reparations for the second world war, he skimmed it and stowed the profit into his Swiss accounts. He stole international aid money, gold from the Central Bank, loans from international banks and military aid from the US. He decreed that more than a million impoverished coconut farmers must pay a levy, to "improve the industry", amounting to $216m. He had already issued decrees to gift most of the coconut trade to one of his own companies; now he stole great blocks of the levy fund, while simuiltaneously receiving kickbacks on government contracts.

RELATED: Why a nation which fought a dictator should not bury Marcos in “Libingan ng mga Bayani”

Eventually, all this theft created a logistical problem: how to handle the huge flow of money. The PCGG archive chronicles how Marcos set up his own banking system, by using cronies to buy private banks and others to control the state banks. They were useful for stealing more money, in loans that would never be repaid, and for obtaining foreign currency – although eventually he set up his own specialist bank to trade currency on the black market.

Most importantly, the banks helped regulate the mass flow of his income. Bank staff would make regular – sometimes weekly – trips to the palace, taking away cheques and bundles of cash, which were then deposited in his accounts. The millions were then funnelled into Marcos’s expanding stockpile of offshore accounts (in Switzerland alone, he had 69). Anywhere in the world, he and Imelda could reach out for their cash - cash that had been wiped clean of its connection to crime.

Multiple houses were provided for the extended family, and they also had a $5.5m yacht, private planes, helicopters and dozens of Mercedes-Benzes. In June 1983, when their youngest daughter wed, they built a new runway and hotel, refurbished a 200-year-old church, demolished nearby houses and rebuilt them in traditional style and imported carriages from Austria and horses from Morocco.

READ ALSO: BBM’s loss a severe blow to Marcos revival

The men and women who work at the PCGG are fueled by their anger. Everyday they discover more details of the family's crimes, while its victims sleep on the pavements and in the slums around them. They are well aware of everything the money could do for the people of the Philippines; if Marcos stole $10bn, it could have paid for the entire government budget for his last year in power three times over.

They want to do more than just retrieve the stolen money - they also want to restore it. It is not easy. The Marcoses, with their money and their connections, have always been one step ahead.

RELATED: El Shaddai endorses Binay, Bongbong

Source: KAMI.com.gh