‘Bolitas’: The seriously strange sexual oddity of Filipino seamen

Nobody sails the high seas the way Filipinos do. The Philippines is a top supplier of seafarers, accounting for roughly a fifth of 1.2 million maritime workers. Being away for months or even years at a time, with only perhaps your ship or your mates as a source of consistency, must lead these seamen to formulate social norms and practises based on what they believe can help them survive.

Their nomadic way of life and unique customs have yet to be studied in-depth, but two researchers have already begun their research on it. And so far, it's yielded interesting results and insights about the mentality of Filipino seamen, and their struggles to stay relevant to maritime trade.

It takes one to know one

When Norwegian anthropologist Gunnar Lamvik first put down roots in Iloilo city, a seafaring sanctuary in the southern Philippines, he felt like he wasn't getting the juiciest, most detailed information there is about the shipping life from his neighbors, who were home on a two-month vacation after 10 months at sea. He reasoned that in order to get to the bottom of an institution's cultural mysteries, one must become part of it.

"It's important to be on board for some time, and build trust. That's the crucial thing to do."

His thirst for knowledge led to three years on and off ships, sailing from one port to another, trying to find and make that connection.

And he really did find it - one night, sailing through the Indian Ocean and immersed in a rowdy karaoke crew party, he belted out the lyrics to "House of the Rising Sun."

Twice.

"That was a real ice breaker." he recounted.

It would be in these kinds of laid-back, half-drunk settings that Lamvik would learn the most about the lives of his shipmates. Soon enough, conversations took a turn to what is probably the most fascinating aspect of the Filipino seafaring identity: the obscure and mysterious sexual practice of bolitas, or little balls.

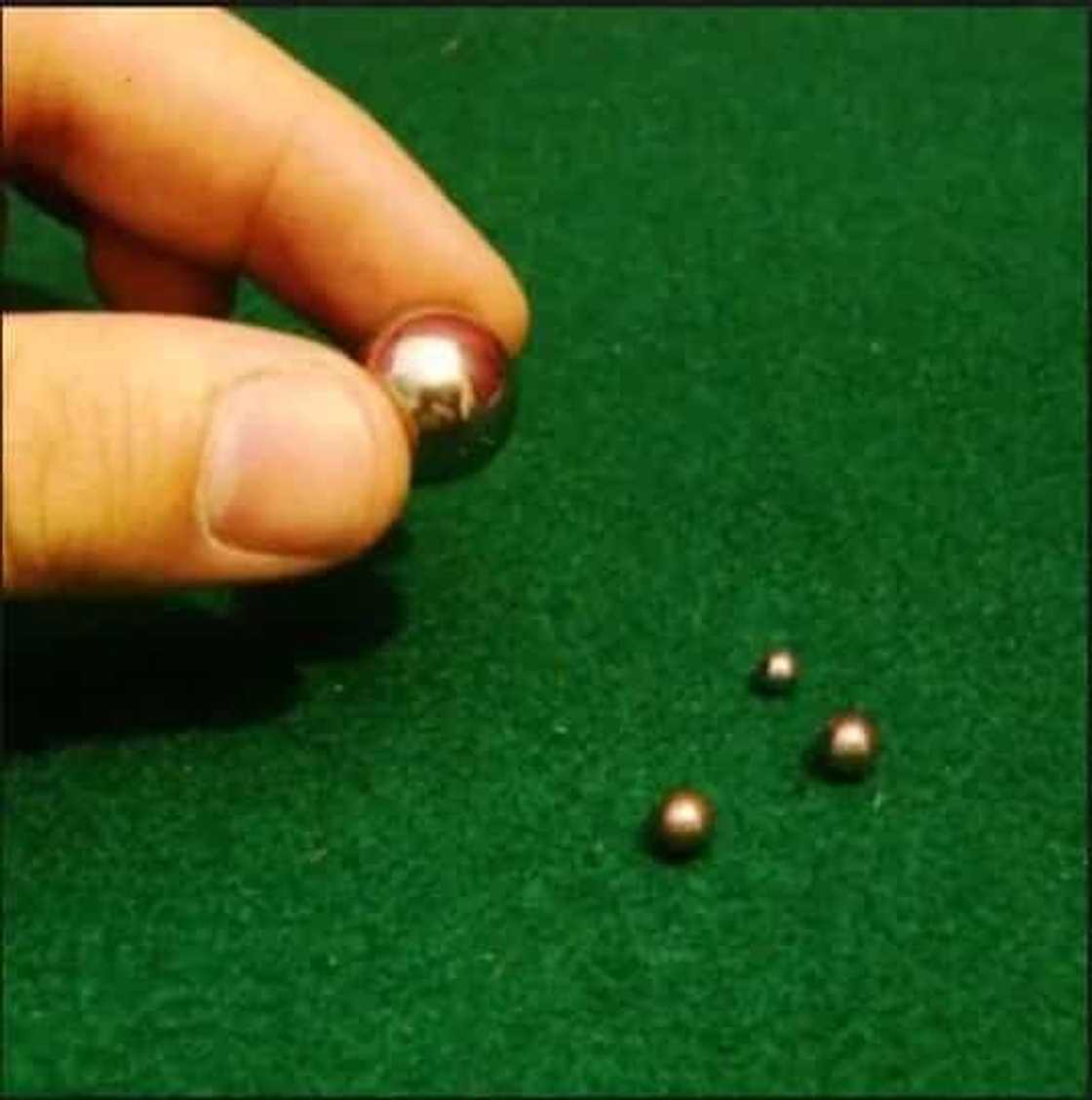

This is a procedure that entails making small incisions on their penises and sliding tiny M&M sized plastic or stone balls underneat the skin. The presence of these little balls is meant to enhance sexual pleasure for prostitutes and other women they come across in port cities, especially in Rio de Janeiro.

No pain, no gain

The second prominent man in this field of study is Steve Mckay, University of California, Santa Cruz's labor sociologist . He's traveled extensively on container ships with Filipino crew members back in 2005 for his research on the masculine identity in the shipping market.

According to Mckay, raw materials for the bolitas range from tiles to plastic chopsticks or toothbrushes. A designated crew member boils the materials in hot water to sterilize them, and then performs the procedure. There are several places insertion can occur on - some have one on the top or the bottom, or on both the top and the bottom. Others reportedly have four - one on the top and the bottom, and on both sides, in "the sign of the cross.'

One sailor is reputedly nicknamed "Seven", for reasons you're sure to pick up.

This practise is unique to Southeast Asia, and dates back to at least the 16th century. No-one is sure, however, if the practise has been continuous.When the Italian scholar Antonio Pigafetta accompanied Ferdinand Magellan and his crew on their exploration, he wrote of a similar practise in modern day southern Philippines and Borneo. It was also reported to have been practised in Thailand and Indonesia, but it petered away around the 17th century, when men were swept away by the influence of Islam and Christianity.

Mckay was surprised to discover that this practise still exists in considerable numbers. However, resources on this topic are extremely limited, so he hasn't got much numbers to deal with in the first place. A study in 1999 found that out of 314 randomly selected Filipino seamen in the port of Manila, 57 percent or 180 of the seamen confessed to having undergone the procedure.

Mckay gathers from his interviews that the danger of infection and resulting pain seem to be worth the attention they get by the multitude of Brazilian prostitutes. It's what they Pinoy seamen are famous for.

What's your edge?

Philippines wasn't always as prominent in the industry; a mere 50 years ago, only 2,000 Filipinos worked in international waters. The oil crisis of the 1970s, however, placed considerable financial pressure on the industry, and an alteration in maritime regulations allowed ships to hire workers from countries with lower wages. Thus, companies set out to reduce labor costs.

Lamvik says the Filipinos emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the best option for the mostly European-owned maritime businesses. After all, he reasoned, Filipinos are Christians, fluent in English, and willing to work for cheaper pay. He draws these conclusions from the experiences of his grandfather and great-grandfather, who both worked on Norwegian ships in their day.

McKay adds that the Filipinos also have an built-in nautical legacy. From the 16th through the 19th centuries, Filipinos were forced into servitude on Spanish galleons, and in the 1800s, they helped commandeer American whaling ships.

Surely, the sea must run in their veins.

Despite this, many Filipinos are keenly aware of their potential displacement. Other low-wage countries such as India, South Korea and Indonesia apply for the same jobs, and for this reason, Mckay posits, the Filipinos feel obliged to up their ante to differentiate themselves from crew members of other nationalities.

The identity the Filipinos have fashioned for themselves is of an adventurous spirit, a creative troubleshooter of machines, and a captivating storyteller. In one of McKay's papers, he mentions a Filipino captain who spoke of the versatility of his country's sailors, especially when things go awry.

"The Filipino, he can fix anything ... Other nationalities, if they see there are no spare parts, they will say, 'okay, that's it, we'll wait 'til we're in port ... but Filipinos somehow will get it working again. They'll make a new part or fix one."

Their awareness that they are easily dispensable have made Filipino crew members insecure and hesitant. Mckay hypothesizes that industry insiders and other international seafarers see this caution as effeminate - a signal that they are disciplined "followers", but not necessarily born leaders.

This, he concludes, has slowed down their upward mobility. The statistics haven't budged much from the mid-1970s: back then, 90 percent of Filipinos working on ships were lower-level crew members, and 10 percent had junior-level office jobs. Fast forward to 2005, and 73 percent still took lower-level roles, while 19 percent had junior office titles. Only 8 percent made it to the senior level.

Filipino captains are still a rare sight.

With this background in mind, bolitas is more than just a physical deformity they took on to please their exotic lovers. It's also an essential element of the Pinoy seaman's larger battle to assert their masculinity, and compensate in a rivalry they can't always win aboard the ship. This competition, McKay explains, started in the labor market, and eventually trickled into their culture. It's a way of dealing with how others perceive them.

In terms of the port competition, however, they're pretty confident they can win, and not just because of the bolitas. Filipino sailors pride themselves on not just appealing to a woman's body, but to her heart as well. They make an effort to treat the prostitutes as more than mere objects in a sexual marketplace, and treating them better than other sailors do.

One Filipino officer explained that the women prefer Filipinos because of their courteous behavior, unlike other nationalities. The Filipino seaman, he says, does not believe he is entitled to treat them badly because he has paid them, but treats them like a lover despite it. "That's what makes the Filipino special. We're romantic."

The shipping life - filled with constant movement and desolate surroundings - is, at the very heart of it, full of danger, boredom and chance. Bolitas and the opportunities it paves for Filipino seafarers act as a welcome diversion, but it also represents a sort of social struggle, a way to be reassured about their status in a life filled with unpredictability.

With the unforeseeable ups and downs of the maritime labor market, accesorizing and enhancing one's masculinity - literally - is sure to be one way to stand out.

Source: KAMI.com.gh